Recognizing and Treating Problematic Fear & Anxiety in Children | John Piacentini, PhD | UCLAMDChat

Hi, I’m John Piacentini. I am a Professor of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at the Semel Institute at UCLA. I also direct the Cares Center at UCLA, which is the Center for Child Anxiety Resilience Education in Support, and this is the center where we work with the community to develop programs to prevent child anxiety and promote resilient children. Today, I’m going to be talking about how to recognize and treat problematic fear and anxiety in children.

And you can ask questions on Twitter using the hashtag #UCLAMDChat, and I’ll be answering–have a few minutes at the end of the talk to answer questions for you, and it’s a pleasure to be here to be doing this for you today. So, what I’m going to talk about today is how to describe and distinguish between normal, mild, and clinically problematic fear and anxiety, to describe some of the signs and signals that your child might have an anxiety problem, and to describe effective strategies for helping your child to manage his or her fear and anxiety. So, first is, what is anxiety, and how do I know if my child has a problem? Well, anxiety is an expectation of something bad happening. So, children that are anxious look a lot like adults that are anxious, and anxiety is really worrying about things that might happen in the future. “Am I going to get sick? Am I going to get a bad grade on this test? Is something going to happen to mom or dad? Are kids going to tease me now?” This is a little different from fear, which–we think a lot about children being fearful and anxious– what fear is, fear is an immediate reaction to an actual threat or a perceived threat, so fear is really in the moment, I see a bee flying at me and I’m afraid I’m going to get stung, I hear a dog barking I’m afraid I’m going to get bitten.

So it really is something that’s more immediate. Anxiety is really worrying more about things that might happen in the future. When we think about anxiety or fears, we think about normal and developmental fears. So, anxiety and fear are really important aspects of us and of animals as well, and anxiety and fear are really nature’s early warning system, kind of our burglar alarm, or our alarm to let us know when something might be dangerous or harmful and to avoid it. So, when we think about different kinds of normal fears at different ages, we can think about infancy–so we know about infants, stranger anxiety or stranger fears–when the infant’s first able to differentiate between different people, they recognize that somebody is new or different from their parent, to their mother, and that will make them anxious–loud noises, also. Early childhood, you tend to see the normal fear is changing a little bit, and that becomes separation anxiety, becomes much more common.

So, children are really attached to their parents or other important figures in their life, and they can certainly be afraid about something bad happening to them or getting separated, and you can see that in little kids, 2, 3, 4, and even older, worrying, always wanting to be with mommy or know where mommy or daddy are. You also start seeing fears of things like monsters, things that kids really aren’t aware of or don’t understand that can also be scary. We’re going to talk a little bit more about what this means just in a minute. Middle childhood–as children are in school, they’re meeting other kids, they’re more broadly engaged with the world. The fears also morph a little bit or change to reflect that.

So they start worrying about real world dangers, kids start hearing about earthquakes or floods or droughts or fires, and they start getting worried about that or kidnappers, and new challenges that come up to them. They may start worrying more about school or how well they’re doing in school because all of a sudden school and academics are becoming more more difficult in adolescence. We all know adolescence is a time where children really–and adolescents and teens–focus their attention more on their peers and how they’re doing relative to other to other kids and others in their social group. So it’s not surprising that the most common normative fears or normal fears in adolescents relate to social status, social group performance to other people like me. “How well am I doing at these different kinds of activities?” These are all completely normal fears that people have kids have. What I want to talk about in just a second is how do you distinguish these typical fears, or these the normal developmental fears, from problematic fears and problematic anxiety? But first, let’s talk about a couple just general points about anxiety in general that characterize anxiety in children.

As I just said, mild fears are very common in children, everybody has fears or worries at different points, and again, these are quite typical. The number of fears tends to decline with age, so young children have a lot of worries about a lot of things. As you get older, you tend to have fewer specific fears, and some of this is because as we get older, we have a better understanding of how the world works, so one, you think about young kids that worry a lot about monsters, or there’s something under my bed at night, when kids are afraid to sleep, or there’s somebody outside my window, and for children, when they hear noises like floorboards creaking or a tree branch blowing against the window, they really want to understand what’s going on, what’s going on with that, so the logical explanation for a lot of kids is that there’s a monster under my bed, or there’s something under my bed, and that actually helps them try to understand what’s going on.

As we get older, we realize it’s not a monster under the bed, it may be the wood creaking, or it may be the wind blowing, so specific fears tend to reduce in frequency over the course of age. Overall, girls report a greater number of fears than boys, but this is age-related, so prior to puberty, boys and girls tend to report the same numbers of fears and have the same kind of the problem with anxiety. It’s pretty similar across boys and girls. Once adolescence occurs and into adulthood, the number of fears and the rates of anxiety disorder are higher in females than they are in males. The manner in which children express their fear, anxiety, and sadness–also which, oftentimes you do see sadness or depression associated with anxiety problems in children is really related to their level of cognitive and emotional development– so young children are more likely to express their fear or anxiety by clinging, by crying, maybe by tantruming, by stomachaches and headaches, a lot of physical symptoms. As you get older, the fear may be –children, they become more cognitively mature, they may be more likely to express their fears to worries and thoughts and things like that.

As I said earlier, fears often change as children grow older. For example, from concrete things like the monsters in the dark, fear of getting sick, to more abstract fears, will others like me, what about my future, what’s going to happen with the world? And again, this just really reflects children as they mature into teenagers and eventually into adults, just the ability to think more abstractly, to think about the future. They have a broader perspective on topics that are on their minds, and their anxieties are going to reflect these topics, and again, the focus of fears tends to change over time, as I said. So, more specific fears for younger children; typically more social anxiety or social fears as kids get older.

That’s not to say that social anxiety or shyness doesn’t occur in young children–it does quite a bit, and specific fears also occur in older kids, so you can have phobias or specific fears of dogs or the dark or things like that, but in general, if we look at the population as a whole, the specific fears tend to be more common in younger kids, and social fear is more common in older kids.

So, let’s start thinking a little bit about–so all these normal fears that kids have, and this is what fears look like in children at different ages, so when do we start talking about problematic anxiety or an anxiety disorder? Well, again, even short episodes of anxiety are pretty common in kids, so your child may have a meltdown or maybe be upset about the first day of school. Being nervous or anxious about that–again, the anxiety that your child expresses is going to be above average, it’s going to be typically more than he or she might express in other situations, but this, again, this is probably relatively normal, and when we think about these anxiety episodes that aren’t really problematic, we think that they’re typically associated with some kind of a circumscribed event, or a specific event. So, going to a new school for the first day, which can be stressful, loud thunder, or a thunder and lightning storm, having to give an oral report in school, maybe experience some teasing at school, or being in new situations where they have to go to their first, say, piano lesson or soccer practice–these kinds of situations are typically associated with some anxiety or some worry.

And some kids may not want to go, or they may refuse to go, they may get upset, but in most children, these are relatively short-lasting, that once they get over these first day jitters, they feel more comfortable, and then the activities that they’re doing may be positive for them and the anxiety will go away. So a child that’s new in school and maybe nervous about going to a birthday party for a classmate because they don’t know anybody– that’s pretty common, but once the child gets to the party, if there’s other kids that are friendly and they’re having fun, their fear is quickly going to go away.

Same thing with child going to their first soccer practice–could be pretty frightening for them, but once they are able to get more comfortable with the team and what’s to be expected of them, then they’ll do fine. So the short-term episodes of anxiety, there’s little outbursts that are predictable, that are related to specific events, again, are pretty normal, usually not something to worry about. So when do we need to start worrying about anxiety? What’s the difference between these normal episodes and more problematic anxiety? Well, there are a couple of things to look for. The first is the intensity of the fear.

So, is the child’s fear response or anxiety response within expected limits? For example, being nervous on the first day at a new school, or is it really out of proportion to the actual threat? Is the child expressing some nervousness, and saying, “Mommy, I don’t know, I’m scared, I don’t want to go to school.” Maybe a little extra clingy, maybe a little bit of crying, again, would probably be considered normal in most situations. But throwing a full-blown tantrum, screaming and yelling, trying to break things, trying to run out of the school, again, that’s a little bit of a greater intensity. A lot of children may be afraid of dogs, you know, walking in the park. If a big dog walks by, the child may cling a little closer to mommy or to somebody, the babysitter, or to somebody else–again, that’s not that unusual.

However, if a little dog walks by and walks up and starts sniffing the child, if the child gets really upset or runs away or starts to cry again, that’s probably out of proportion to the potential threat of that dog. So we’re looking for intense fears that are surprising in, kind of, the degree or intensity of the response to the situation. The frequency of fears is another important thing to look for. So, again, the first day of school– even the first few days or the week or two of school might cause some nervousness in the child. If these fears or nervousness lasts longer than that, if it’s going on for several weeks or month or longer, again, that may indicate some kind of a problem.

If the child is starting to get upset about things, tantruming, clinging, crying multiple times a day or multiple times a week over the same situation–again, that may indicate that there’s some kind of a problem. Is the context of the fear focused on an innocuous situation? It’s one thing to be afraid of a bulldog that’s barking or snarling–that’s actually appropriate. It’s another thing to get really upset about a cartoon dog, cartoon that has a picture of a dog in it, or a picture of a dog in a book, or a small little dog. Or a child going to the birthday party of somebody that they know well, or a friend, or visiting cousins– again, if the situation–if you look at the situation and it’s hard to figure out why the child might be afraid in that situation, that might be an indicator of more problematic anxiety.

And does the fear occur spontaneously? So when we think about about normal fear or normal anxiety, typically, it’s triggered by something that we can understand–as I’ve said, first day of school, seeing a scary dog, trying something new for the first time, having to give a report in class, for example–some children may express fear, panic attacks, or just crying or upset or clinging or worrying for no apparent reason, it just comes on out of the blue, and in these situations, again, we’re looking, thinking that this might be something that could indicate a problem.

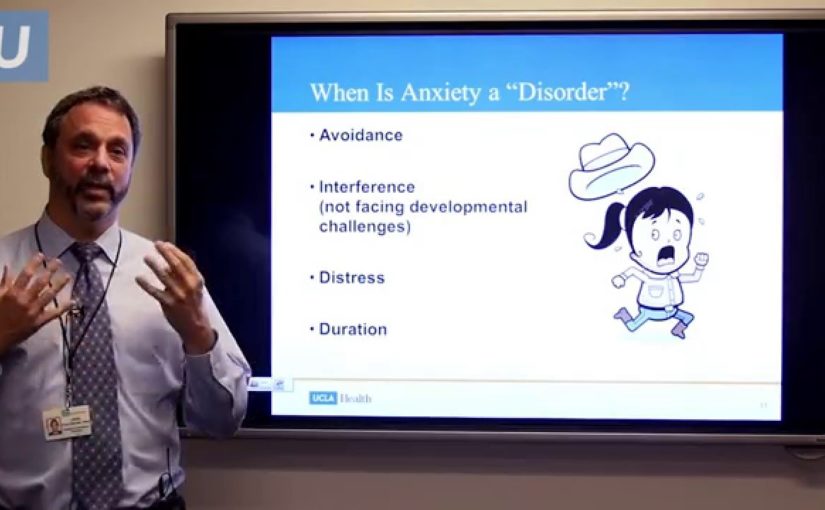

So we have normal anxiety, we have problematic anxiety. When is anxiety actually a disorder? So, we’ve heard of anxiety disorders, and this would be something that probably would warrant intervention, and there are a number of factors that we’re going to be looking at. When the anxiety leads to significant avoidance– so if the child refuses to go to school, the child refuses to go to piano lessons or to go to play in the soccer games or baseball games for their team, the child refuses to go to birthday parties, the child may even refuse to want to be around their cousins or other people that they’re familiar with, the child refuses to go to the park because they’re afraid that there are going to be dogs at the park– when we see the anxiety resulting in the child starting to avoid important things or things that they should be doing, again, that’s when we think that it might be time to talk to somebody about getting help.

Similar to avoidance is interference–when the anxiety really starts interfering in with important aspects of the child’s life. And, again, this would be the same thing. School–if the anxiety is causing the child to be so upset in school that he or she can’t do their work or be involved in other activities, or if the child is actually missing a lot of school because of anxiety, again, that’s a problem. We see a lot of children oftentimes will go to the school nurse or go to the office and ask to call their parent to be picked up, complaining of like stomachaches or headaches or other kinds of things. When we see patterns like this, again, that suggests to us that there probably is something that needs to be looked at.

In terms of other types of interference, we can think about interference in terms of social functioning– so if we think about the job of being a child, what’s the job of being a child? The job is to go to school, to learn, so to prepare them for the world, and also to develop social relationships so that they can have friends, they can learn how to get along with others, how to negotiate with others, how to plan, how to organize things. And when children that are anxious–especially children with social anxiety–start avoiding social situations, or if the anxiety interferes with their ability to have friends or to keep friends, again, that’s a problem, and that’s something that we’re going to think about, it’s time to maybe look for treatment. Distress is another thing that we’re looking at, so–it’s one thing for the child to tantrum or get upset before school, the first few days of school. If they become really upset, if the anxiety is really distressing, really troubling, or upsetting to them over longer periods of time, that’s something we’re thinking about maybe problematic, and it’s not only distress for the child, it’s also distress for other family members.

If the child’s anxiety begins to interfere with the functioning of other family members–all of a sudden, the family can’t go out to dinner, they can’t go to the park, or can’t do fun things that they like to do because the child is too upset or anxious, again, that could be a problem. And that can really be distressing to parents or to siblings as well. If siblings aren’t able to have a friend come over to play because it will upset their brother or sister who’s anxious about being around other people, again, that can be both upsetting, distressing, and interfering.

And finally, duration. So, we talked about duration. It’s okay to be nervous the first few days of school. If the anxiety lasts, you know, for weeks or months or longer, again, that’s something that we would look at as potentially troubling. So if your child has anxiety that isn’t really interfering, it’s a little bit upsetting but it usually goes away or resolves, that child may be okay, that might be fine, the child may grow out of that anxiety. If the anxiety is leading to avoidance of important activities, if it’s leading to interference with the child’s ability to make or keep friends, with their schoolwork, or kind of typical family functioning, if the child is is overly distressed, or other family members are distressed by the child’s anxiety, or if the anxiety is lasting for longer periods of time, these are all signs that the anxiety may be problematic enough to look for help. So how common are anxiety disorders in children and adolescents? So we’re talking about children that actually have anxiety that meets these prior criteria that is sufficient enough to cause interference in their life and to possibly trigger on treatment.

Well, it’s really the most common child psychiatric disorder in the country. If you look at all the different anxiety disorders combined, up to about 12%-20% of children, based on large-scale surveys–and this isn’t surveys of just kids in clinics, this is surveys of kids in schools and in the community–up to 12%-20% of kids in the community suffer from anxiety that may be interfering with their lives in one or another ways. So, let’s think. If you look at a typical classroom–I mean, that may be 3-5 kids or more in every classroom on average would suffer from some significant anxiety disorder, and when we think about the different types of anxiety disorders, some are more common than others, and I’m going to talk just a little bit about some of these more common disorders, but separation anxiety social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are typically the most common disorders that we see. Also, specific phobia. So a specific fear of dogs, heights, the dark, etc. can be quite common. Other disorders that we see in children are obsessive-compulsive disorder–it’s also reasonably common, less than the others, selective mutism–when children are afraid to talk or unable or refuse to talk in school or in social situations although they’re able to talk at home– we see is about 1% or 2% along with OCD, and then agoraphobia, which your children are afraid to leave home, or panic disorder–children that have recurrent panic attacks for no reason–these are less common in children.

So, let’s talk about some of the more common disorders and what they really look like. So, separation anxiety disorder is basically a disorder in which the child is afraid to be apart from parents or other major attachment figures, such as a grandparent or somebody else that’s really involved in taking care of the child because they’re afraid that if they separate or are separated from their parent or this other major attachment figure, something bad is going to happen to them or to the parent, and they’ll never see each other again. So they worry a lot about bad things happening to others. They worry that something bad is going to happen to them, they’re going to get lost if they go out to the store, or that when they go to school, they’re going to get kidnapped, or something’s going to happen to the parent when parents go out at night or parents are out running errands, or at work that something bad might be happening to them and the child will be left alone.

These children are afraid to be home alone. They oftentimes will follow mom or dad around the house. They may be very clingy, they may not want to be left in the room by themselves, difficult sleeping alone at night. Separation in children are the children that always want to get in bed with the parent or have a parent sleep with them, and they also complain a lot of physical symptoms like headaches or stomachaches, and these–often it’s headaches or stomachaches– are used an excuse to stay home from school, and this is a reasonably common disorder. You know, we think about separation anxiety occurring in younger children, and it does, but we also see separation anxiety in teenagers, and actually, now we recognize that separation anxiety can also occur in adults, so we can have maybe a spouse or an adult child living with parents that might be worried about bad things happening to another family member.

So you tend to see the separation anxiety in terms of the different symptoms that you would look out for in young children. They’re just pretty explicit. They’re worried about something bad happening to Mommy or Daddy. There’s–something bad might happen to them. They may have nightmares about being separated, they may refuse to go to school or not want to go to school. Children, when they get a little bit older, they get extremely upset when a parent tries to go out. They’re going to be left with the babysitter.

That can lead to tantrums and screaming and yelling, and a lot of cases, parents are stuck staying home. And then older kids, even teenagers and in high school, tend to also want to stay home from school and describe a lot of stomachaches and headaches and other physical complaints. Another common disorder is social anxiety disorder, or social phobia, and what social anxiety is, it’s a marked and persistent fear of social situations in which the child or the teen is going to be exposed to new people or possible evaluation. So really, what this cuts down to is a child or a teen saying I don’t want to talk to people, I don’t want to go to parties, I don’t want to give book reports, I don’t want to be in public because I’m afraid I’m going to do something really embarrassing or humiliating and it’s going to be really, really upsetting.

So this is like an extreme, extreme form of self-consciousness, and in being exposed in situations in public, the child or adolescent can become extremely anxious. They will try to avoid these situations as much as possible. It really leads to a lot of interference in functioning, and to give this as a diagnosis, the symptoms need to be present for at least six months. So when we think about that, how social anxiety looks in different children, maybe can begin as inhibited temperament. So these are the really clingy, shy children that you tend to see, even as very, very young babies, may be associated with selective mutism–as I said, children that are afraid to, are unable to talk in public settings, although they can talk at home, and then rates of social anxiety disorder tend to increase with age, so it’s more common in adolescents.

And it’s also quite common in adults, and a lot of adults who have social anxiety disorder report that the symptoms first began when they were in adolescence. What are some of the commonly avoided situations we see with social anxiety disorder? Parties, meeting new people, entering a group of peers, talking one-on-one, dating, certainly, being assertive, standing up for themselves, having to do a performance like a book report, a piano recital, a soccer game, or baseball game– extremely difficult for youth with separation and social anxiety disorder–and even eating in public or using public restrooms, writing in public at school, can all be signs of social anxiety disorder.

So the third disorder I’m going to talk about is generalized anxiety disorder, and as the name suggests, these are children that are worried or afraid about just about everything, so it’s excessive anxiety and worry that it is almost always present, and it’s worry about a number of different things. So, kids with generalized anxiety disorder worry about how well they are at other things, am I as good as other kids, am I good enough in sports, am I good enough in school. They worry about being on time, they worry about the family running out of money, they worry about parents getting a divorce even when there’s no problems at home, they worry about the Middle East, they worry about world events. These are kids that really worry about just about everything. The worry is really difficult to control, and the worry is oftentimes associated with physical symptoms like fatigue, restlessness, difficulty thinking, difficulty sleeping, muscle tension, as you might expect, because these kids are always tense or anxious.

So kids with generalized anxiety are very self-conscious. They require frequent reassurance, so one of the tell-tale signs of generalized anxiety disorder is constant reassurance seeking. “Am I going to be okay? Is this okay? I’m worried about this bad thing happening.” A lot of what-if questions. “But what if this happens? What if I get lost? What if I run out of lunch money? What if a burglar breaks into the house? What if something bad happens at school?” What if, what if–they really worry a lot about the future, and they’re trying to get reassurance that things are going to be okay.

Unfortunately, the reassurance doesn’t work, and the kids continue to worry. So how does anxiety interfere at school, which is oftentimes where the symptoms may be maybe initially picked up? So, when we think about generalized anxiety disorder, we think about excessive worry about schoolwork, friendships, schedules, procedures, things that they need to do, health, and they’re asking the teachers or other people at school for reassurance or repeatedly asking questions to make sure that things are going to be okay.

Social phobia, or social anxiety, again, has significant impacts at school because children try to avoid school, or they try to avoid participating in class or speaking in class. I mean the socially anxious child’s worst nightmare is getting called on by the teacher, even if they know the answer, so they oftentimes tend to shrink down and try to be unnoticed. Very worried about doing something embarrassing in front of other kids. They may avoid the lunchroom. They may avoid recess and go in the library or hideout somewhere because they’re afraid, again, of doing something dumb or embarrassing or being humiliated in public. And then separation anxiety disorder also–worrying about something happening to parents. So if a child is in class all day worried about being separated from Mom or Dad, they’re not going to be able to concentrate on their schoolwork. They also oftentimes will go to the nurse with stomachaches or headaches to get picked up, and they will try to avoid school whenever they can.

So, these anxiety disorders really do have significant impacts in school, and looking at this list, you know, it’s easy to imagine the kinds of impacts or impairments that these disorders can cause socially or also cause at home or with or with family. Now, we’ve talked about school refusal and children not wanting to go to school because they’re worried about social anxiety, they’re worried about something bad happening to Mom or Dad, and those are really common reasons why children refuse school, but school refusal is much broader than that, and there are a number of factors that need to be looked at if your child is refusing to go to school or only goes under extreme distress, and there are a number of things in addition to anxiety.

So, separation fears are something that we would need to assess. Is it because the child is afraid of bad things happening to child or to mom? Social anxiety, they’re afraid they’re going to have to talk to other kids or be called on in class. Some children have test anxiety, they get extremely nervous when they have to do a test, even if they know the material. Even if they’re really smart and well-prepared, when they sit down to do the test, they get so anxious that they don’t do well. Other children may be bored or demoralized they have learning problems, ADHD, that may make school hard for them. Bullying or teasing at school should also be something that would be looked at, and as I said, learning problems may be another issue. So if your child has a problem with school refusal or doesn’t want to go to school, anxiety, is it may be that there’s anxiety underlying this issue, but there may be other issues as well that need to be identified? What are some of the warning signs for problematic child anxiety? So we’ve gone over a number of factors, but there are a couple of more specific things to look for.

When we’re thinking about trying to identify anxiety, extreme shyness is certainly a marker or risk factor for social anxiety disorder. Isolation–again, if the child is afraid to be around other people because of social anxiety, they want to stay with parent, they’re going to avoid doing things with friends, going on playdates, and other kinds of things like that. Avoiding social situations, extreme discomfort when the center of attention, avoiding schoolwork, not wanting to do schoolwork or doing other kinds of activities for fear of making a mistake– this is something common in generalized anxiety, sort of, the kids are afraid of making mistakes– children with anxiety expect bad things to happen. They worry about upsetting others, often ask questions or ask for reassurance a lot more than other kids. Perfectionism is something that we see in anxious children. Excessive worry about failure–again, this fear of making mistakes or bad things happening, and you can also see children that are nervous or tense, that they may be jittery, shaky, high-strung, unable to relax.

That may also indicate that there’s an anxiety problem, and then children with anxiety often lack self-confidence. Physical symptoms we’ve talked about–physical symptoms like trouble catching breath, stomachaches, or headaches, nausea, sweating, dizzy, faint, or lightheadedness, increased heart rate–if you’re anxious, your heart’s going to beat faster– maybe harder catching your breath, you may be more likely to sweat, and we want to look at the functional role of physical complaints. So what does this mean? Well, that would be, if the child complains of these symptoms, what happens? Does something good happen? Or does something bad happen? So, children that complained of stomachaches or headaches on school mornings, or they complain about the day that they’re going to have a test or have to do an oral report in class, they complained of stomachaches or headaches and they get to stay home–that serves to reinforce these headaches because the headaches or stomachaches or physical complaints will keep them from being in anxious situations, and that’s a good thing to the kids, so a lot of times when children do develop these these physical symptoms as part of their anxiety, over time they may learn that the symptoms are able to get them out of doing things.

So if they don’t want to do something, if they’re afraid to go to the soccer game or the piano recital or go to the birthday party, they complain of feeling sick, and they’re allowed to stay home. That’s important to look out for when we’re screening anxiety. If you’re thinking about, “Does my child have a problem with anxiety?” there are a couple of questions that you can ask. Does your child worry or ask for reassurance from you almost every day? Does your child consistently avoid certain age-appropriate situations or activities or avoid doing these things without a parent? Does your child frequently have stomachaches, headaches, or episodes of hyperventilation? And does your child have daily repetitive rituals that we might find an obsessive-compulsive disorder? Things like repetitive hand washing, or needing to organize or arrange things in certain ways. Now, if you can say yes to any of these questions, that doesn’t mean that your child has an anxiety disorder, but it means that it’s something that you should watch out for, some of the other things that we’ve been talking about, and if so, then that may be the reason to contact a mental health professional to get some advice on what to do.

So we’ve talked about what anxiety is. I just will have the last couple of minutes. I want to talk about what are some ways to manage child anxiety and are some things that you can do to manage your child’s anxiety. Well, first of all, we need to understand a little bit better about how anxiety works, and when we think about the anxiety we think about anxiety being expressed in 3 different ways, we call these the 3 channels of anxiety. The first channel is thoughts, so children with anxiety tend to worry, they have negative or biased thoughts. So people with anxiety–children and adults–tend to see the world as a more dangerous place.

They tend to see neutral things, or even positive things sometimes, as potentially dangerous. For example, going to a birthday party, going to Six Flags with friends–that would be fun to most kids– but to an anxious child, they might worry about getting sick or getting hurt or getting lost at Six Flags, or they may worry about not having any friends or people making fun of them at the birthday party.

So this negative or biased thought is very characteristic of anxiety. And poor concentration–if the anxiety is making them worry, they’re going to have less ability to concentrate on the other things that are going on, like at school. Feelings or emotions or physical symptoms are the second channels, so physical symptoms like headaches, stomachaches, sweating, heart racing–are another way that anxiety is expressed, physically through the child’s body. And we can also add emotions here as well, so feelings of fear, worry, or feelings of fear, for example–and then behaviors. So the third channel is children with anxiety express their anxiety through some behaviors: avoidance– trying to avoid things or staying home, clinging, crying, tantrum, and the like, so we want to pay attention to both the thoughts that are associated with anxiety, the physical feelings associated with anxiety, and the behaviors.

And in treatment, and what you can see–I guess this slide didn’t come out exactly right– but you can see that each of these circles–thoughts, feelings, and behaviors– all interact with each other. So if my thoughts get worse I start thinking about anxiety or something bad happening, that’s going to make my body, my heart rate starts racing faster, maybe I’ll get more short of breath, and that may lead me to start crying or clinging to Mom or avoiding things, and that they will lead my thoughts getting even worse and my feelings getting more pronounced and my behaviors getting more extreme, and you can see how that’s going to roll into a tantrum. And as an example–here we go– you can see this a little bit better here, the circle goes round and round and round, and the more scared I start getting in my thoughts, the more my body’s going to react in becoming more extreme, in terms of heart beating, etc., which is going to lead to more anxious behaviors, and again, that goes around and it gets worse.

So as an example, for a child, giving an oral report in class is going to say the kids are going to think I’m stupid, and that’s going to lead to sweating and shaking and heart flushing. It may lead to avoidance or freezing, the child’s up in front of the class not being able to say anything, shaking– now they’re going to think I’m stupid, and that’s going to lead these physical symptoms to get worse, and that’s going to lead to even more avoidance, and the child’s really paralyzed now, and it goes around and around and around and it gets worse, and worse so in treatment, what we want to do is break the connections between the thoughts, the feelings, and the behaviors.

And the way we do that is through something called cognitive behavior therapy, and in children, when we’re working with cognitive behavior therapy, oftentimes we will work on changing the thoughts and the feelings first by giving the children–so in terms of doing work with the feelings, we’re going to teach the children how to use deep breathing, muscle relaxation strategies, stress management strategies to reduce their heart rate, to calm their bodies, and then we can work with them to generate more positive thoughts, coping thoughts, how can they cope and turn these negative thoughts into more positive thoughts, and once we have them calm, and once we have them thinking more clearly, then we can work on the avoidance behaviors by helping them give book reports or playing soccer games, etc.

So, it’s a very systematic type of treatment that we’re doing with these kids. The other thing that’s incredibly important to know about anxiety is something we call the anxiety cycle, and what we typically see when children are anxious is–it’s time to get up for school, say, for a child with separation anxiety, and the child starts worrying about something bad happening to Mom, or I have to give a book report in school, they start getting worried, and they get a stomachache, and they get upset, and they don’t want to go to school, and they may tantrum, and finally Mom or Dad just says forget it, just stay home. And what happens when they stay home? The anxiety goes away because the dangerous situation is gone. What this does is serves as negative reinforcement, and what negative reinforcement is, is if I do something and it makes a bad thing go away, I’m going to do that more and more, because it’s like a reward, and the bottom line is the more you give in to your child, the worse the anxiety gets.

So if I let my child stay home when she’s anxious about going to school, that’s going to teach her that she can stay home from school by just tantrums, and every day, if she tantrums and I let her stay home, then she’s learning that tantrums are good, tantrums keep me home, tantrums keep me safe. So the more we give in to the tantrums, the more we’re teaching the child to use tantrums to stay home. In treatment, we want to break this cycle, and we want to–even if the child is upset, she still needs to go to school, or he still needs to go to school, we don’t give in to the tantrums, and again, this is something hard to do on your own if your child is having significant tantrums, but in treatment, this is what we would work on.

But there are a couple of things, as my last two slides– there are a couple of things that you can do to try to break these cycles, and they are as follows: reward your child’s courageous behaviors–so as parents, we oftentimes tend to the things that worry us, so we pay more attention to the anxiety or to the negative behaviors than we do to the positive behaviors. We want to catch our children being courageous and encourage our children to be courageous. We may start with little things. It may be too much for the child to go to the soccer game, but maybe we can go to the playground with the child instead. Avoid giving in to your child’s fear behaviors. This is what I was just saying before. Don’t give in to their attempts to avoid things they should be doing. Children need to go to school. Children need to go to piano practice and soccer practice, because the more they go, over time, again, with the appropriate, you know, coping strategies and support, then the activities should become more familiar, should be more fun for them, and their anxiety will decrease.

Teach your child how to communicate, how to cope, and how to problem-solve, and you can model this, you know, “Some things make me afraid too, but I just know that I can get through it, and I want to go see, so you may assume that something bad is going to happen, but let’s go see because the chances are that nothing bad will happen.” And again, for parents, the Most Important thing that you can do is to control your anxiety. It’s so important because as parents– and I’m a parent–and when our children are upset, we worry about those things, and the children see that anxiety. When they see us worrying, that makes them even more worried because now they think there’s something real going on, so we want to be brave, we want to control our anxiety even if we’re worried about our children.

That doesn’t mean we can’t worry about our children. It just means we have to worry about them where the children can’t see that. So we’re being anxious, we’re being brave, and we’re encouraging and supportive of our children. It’s going to be important. That’s going to be helpful in terms of treatment, and then the final thing is when you get in these situations with a tantrum, the child is trying to avoid, what can you do? Well, the important thing is you want to disengage from the tantrum at the earliest possible point. If the child’s going back and forth, the worst thing you can do is get into a screaming match because the kids usually win the screaming matches, or if they don’t, by the time you’ve escalated to the point screaming, screaming, screaming, screaming, whoever winds up here, it’s going to be a pyrrhic victory because everybody’s so riled up about this.

So what you want to do is avoid engaging in back and forth arguing. “You’re going to school,” “You’re going to soccer, here are your clothes, I’ll be back in a minute.” And try to avoid the back-and-forth. Now, when you try to disengage in this way, typically the child’s behavior is going to escalate, it’s going to get worse, but it’s important to wait that out. You want to avoid it, maintain a calm and non-emotional reaction. If you’re getting upset or angry, that’s going to make the child more upset or angry. We want to be neutral, we want to just avoid punishment and stay calm, and the calmest participant in these activities is going to win. If you can keep your calm, the child will eventually give up. If you get upset, then the child is is is more likely to win. As soon as the child calms down, even for a second, even for a moment, then you can engage him or her in a different activity.

The child’s tant truming, you’re screaming, and if they just stop and settle for a minute, you can say, “Great. Let’s go get breakfast,” or “Great. Let’s do something else.” You want to take them out of the moment and engage in something that’s maybe a little bit more positive. And then you can work with them from that sense. And it’s okay to include a discussion of the event, to talk about what happened, but you don’t want to do it at the moment. You can’t do it at the moment when the child’s upset. The goal is that the child needs to calm down, and then you can talk to them about the event. These are all things that are done in cognitive behavioral therapy, which is an evidence-based treatment for anxiety. It’s the most well-tested treatment for anxiety, and it is what’s recommended for children with this problem. So I’m going to stop here, and I want to thank you for your attention, and I hope this was helpful.

So I see we have a couple of questions here from Twitter. The first is “Is anxiety a genetic disorder?” Well, there’s been a lot of research showing that anxiety does have a genetic basis in some, but not all, cases. So we know that anxiety tends to run in families. Parents of anxious children are more likely to have anxiety, and there has been some research identification with anxiety, we’re not quite there yet. But yes, anxiety does have a genetic basis, but that doesn’t mean that all anxious children have this genetic basis. We know that genes or genetics accounts for a proportion of children with anxiety, and in terms of treating children with anxiety, it doesn’t make a difference if we’re using treatment, for kids, whether or not they come from an anxious family or not, so the fact that it might have a genetic basis in one child doesn’t make treatment more difficult with them. It is important, though, to include parents in the treatment of anxious children regardless of whether there’s a genetic relationship or not because parents are so important in helping children manage anxiety, as I just said in the last couple of slides.

“What are the long-term effects of child anxiety?” Well, untreated, anxiety can stay chronic for a long time, and most adults with anxiety have the onset of their anxiety at some point in childhood. So it doesn’t necessarily go away by itself in all cases. In many cases, it will get better, it will resolve, but in a proportion of cases, it will stay and maintain for long periods, which can be significant because if you think about an adult with social anxiety disorder, again, they may not be comfortable in social situations, which may limit their ability to maximize their education to get the best possible job that they can get, and we do see there’s a higher risk over time, with untreated anxiety, for the individuals to develop depression and even use alcohol or other substances to help manage your anxiety.

So there are some considerable risks. In severe cases of anxiety, a lot of children with treatment, they’ll go on to lead normal lives. “Does the brain of someone who suffers from social anxiety differ from a normal brain?” Well, there have been some studies looking at different areas of the brain, I mean, social anxiety–and there are some findings from neuroimaging studies and from similar kinds of studies suggesting there are some specific parts of the brain or circuits of the brain that may be overactive in individuals with anxiety, and this is really exciting work, and we’re hoping that we’re going to be able to develop better treatments as a result of this. And, “What literature can I read about anxiety?” Well, there are some great places to get more information about anxiety. One place is the carescenter@ucla.edu website, where we have information on that.

There are some other great books and sites, as well. If you go on Amazon, there are some books on the anxiety that you can look at on child anxiety and about how to parent children with anxiety, so there are a lot of really great resources out there, and websites that you can find. And I think that is it. So, our time is up, and thank you very much…